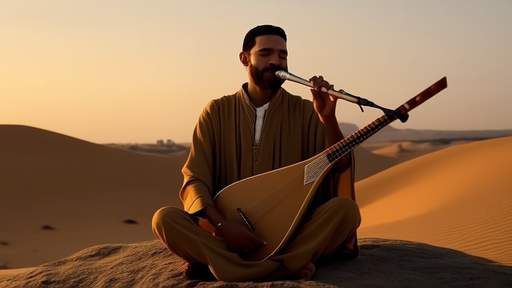

The haunting, reedy tones of the arghul, a traditional double-pipe reed instrument from Jordan, have echoed through the deserts and villages of the Middle East for centuries. Unlike its more widely recognized cousin, the mijwiz, the arghul possesses a distinct acoustic character due to its unique dual-pipe construction. One pipe serves as a drone, producing a continuous harmonic foundation, while the other delivers intricate melodic phrases. This interplay creates a rich, layered sound that has been integral to folk music, spiritual ceremonies, and communal celebrations across the Levant.

What sets the arghul apart from other wind instruments is its acoustical complexity. The drone pipe, typically longer and lacking finger holes, resonates at a fixed pitch, providing a tonal anchor. The melody pipe, equipped with several finger holes, allows the musician to craft fluid, expressive lines. The interaction between these two pipes generates a phenomenon known as beating, where slight variations in pitch produce a pulsating effect. This acoustic quality gives the arghul its signature hypnotic and meditative sound, often described as both earthy and otherworldly.

The materials used in crafting the arghul also contribute to its distinctive voice. Traditionally, the pipes are made from arundo donax, a type of cane that grows abundantly in the region. The reeds are carefully selected for their density and flexibility, as these properties influence the instrument’s timbre and responsiveness. Modern variations sometimes incorporate synthetic materials, but purists argue that natural cane yields a warmer, more organic tone. The mouthpiece, usually a simple double-reed design, requires precise control of breath and embouchure, making the arghul as challenging to master as it is mesmerizing to hear.

In performance, the arghul’s acoustics are deeply intertwined with the player’s technique. Skilled musicians employ circular breathing to sustain the drone uninterrupted while articulating melodies. Subtle adjustments in air pressure and lip tension allow for microtonal inflections, a hallmark of Middle Eastern music. The instrument’s dynamic range is surprisingly broad, capable of whispering delicately or projecting powerfully across open spaces. This versatility has ensured its enduring presence in both rural folk traditions and contemporary fusion projects.

The cultural significance of the arghul cannot be overstated. Historically, it accompanied storytelling, weddings, and Sufi rituals, its vibrations believed to bridge the earthly and the divine. Today, while electronic instruments dominate mainstream Arab pop music, the arghul persists as a symbol of heritage. Ethnomusicologists study its acoustics to preserve fading musical practices, while experimental musicians incorporate its drones into avant-garde compositions. The instrument’s survival is a testament to the enduring power of acoustic authenticity in an increasingly digital age.

From a scientific perspective, the arghul offers fascinating insights into harmonic acoustics. The relationship between its drone and melody pipes exemplifies the physics of standing waves and resonance. Researchers have analyzed its sound spectra, noting how the overtone series interacts with the surrounding environment—whether a stone courtyard or a vast desert—to create immersive auditory experiences. These studies not only deepen our understanding of the instrument but also inform broader work on wind instrument design and psychoacoustics.

Despite its niche status globally, the arghul has found unexpected admirers beyond the Arab world. European and American musicians drawn to its primal resonance have adopted it into genres like ambient, drone metal, and world fusion. Workshops from Amman to Berlin now teach its construction and playing techniques, ensuring that new generations can explore its sonic possibilities. Yet, for all this cross-cultural interest, the soul of the arghul remains rooted in the landscapes and traditions of Jordan, where its voice still rises with the wind.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025