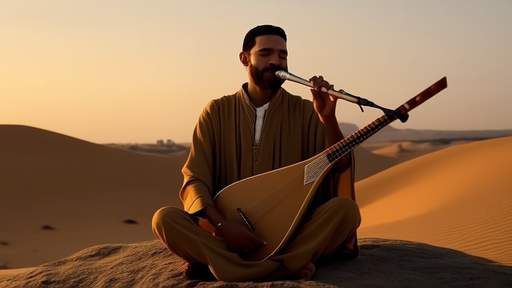

The haunting melodies of the simsimiyya, a traditional lyre-like instrument from Yemen, have echoed across the Red Sea coast for centuries. Its metallic twang, both melancholic and uplifting, is inextricably tied to the fishing communities of Al-Hudaydah and Aden. Yet beneath the surface of this cultural treasure lies an unexpected adversary: the slow, inevitable decay of its iron soundbox. Rust, that most mundane of chemical reactions, has become an unlikely antagonist in the story of the simsimiyya’s survival.

Unlike the wooden frames of most stringed instruments, the simsimiyya’s resonator is traditionally forged from scrap iron—old ship hulls, discarded tools, or whatever metal could be salvaged by coastal blacksmiths. This choice of material wasn’t merely practical; the iron body gives the instrument its distinctive bright, percussive sustain, a sound that cuts through the salt-laden air like a fisherman’s call to prayer. But the very environment that shaped the simsimiyya’s voice—the humid breezes of the Red Sea—also conspires against it. Within years, sometimes months, reddish-brown blooms begin creeping across the metal surface.

Older musicians speak of instruments lasting generations, but today’s luthiers note a disturbing trend. "The rust comes faster now," says Ali al-Mahmadi, a third-generation simsimiyya maker from Al-Makha. "My grandfather’s tools could resist the sea air for a decade. Now, even with oiling, the new metals corrode within three monsoons." The culprit, researchers suggest, isn’t just humidity. Increased salinity in coastal air from declining fish stocks (forcing fishermen further offshore) and the chemical composition of modern scrap metal play roles. What was once a slow patina of age has accelerated into a destructive force.

Traditional preservation methods reveal a quiet ingenuity. Fishermen rub the iron bodies with shark liver oil—a practice dating back to when pearling divers repurposed their leather satchels for instrument cases. The oil’s unique lipid composition creates a water-resistant barrier while minimally affecting resonance. In the Tihamah region, some players bury their instruments in dry sand between performances, exploiting the desert’s latent aridity. But these solutions are becoming inadequate against the onslaught of modern environmental changes.

Conservators at Aden’s National Museum face a paradox. While treating a 19th-century simsimiyya, they discovered that removing all corrosion destroyed the instrument’s voice. "The rust layers had become part of the acoustics," explains curator Fatima Abdullah. "When we cleaned it to bare metal, the fishermen said it sounded ‘too young’—like a boy trying to sing a grandfather’s song." This revelation has sparked debates about whether preservation should prioritize material integrity or sonic authenticity, a dilemma familiar to restorers of church bells and gamelan gongs.

Modern metallurgy offers potential solutions. Stainless steel alloys could outlast iron by centuries, but preliminary tests show they produce a harsh, metallic timbre lacking the warm decay of traditional instruments. Some experimental luthiers are coating iron bodies with graphene-based sealants, while others advocate for controlled rust stabilization—a technique borrowed from maritime archaeology. Yet each innovation risks altering the intangible qualities that make the simsimiyya’s sound a cultural touchstone.

The rust creeping across these iron soundboxes mirrors larger erosions. As younger Yemenis migrate inland or abroad, the knowledge of maintaining the instruments disperses. YouTube tutorials now teach diaspora youth how to oil their simsimiyas with olive oil when shark liver is unavailable—a small adaptation in a chain of cultural transmission stretching back to the incense trade routes. The very corrosion that threatens the instruments has become a metaphor for resilience; like the fishermen who play them, the simsimiyya endures by adapting while keeping its soul intact.

Perhaps there’s poetry in this slow oxidation. The simsimiyya’s rust isn’t merely decay—it’s the instrument recording its own history, layer by microscopic layer. Each crystalline flourish of iron oxide alters the vibrations ever so slightly, letting the metal sing not just with its forged voice, but with the accumulated whispers of every storm season it has weathered. In a land where oral history is sacred, the simsimiyya’s body literally encodes its past through chemistry, playing back memories in a language of resonant corrosion.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025