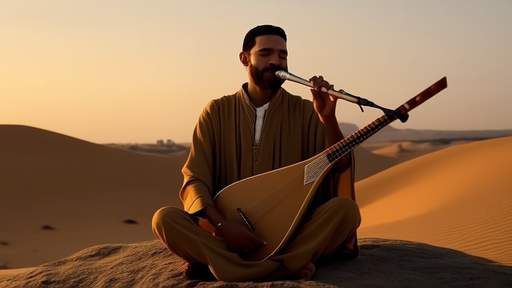

The haunting melody of the algoza, Pakistan's traditional double-flute, carries within it centuries of cultural resonance. Unlike single-pipe wind instruments, this twin-reed wonder produces a hypnotic interplay of harmonies, its very structure embodying a profound philosophical and aesthetic symmetry. To encounter the algoza is to witness sound made visible – two parallel bamboo shafts, bound yet independent, breathing as one.

Carved from a single piece of sheesham wood or aged bamboo, the instrument's physical form reveals its essence. Each pipe measures approximately 14-18 inches, their lengths meticulously matched to maintain tonal equilibrium. The left pipe (murdunga) typically carries the melody, while the right (dodh) provides a continuous drone, though master players fluidly alternate roles. This duality mirrors Sufi concepts of complementary opposites – the mortal and divine, separation and union – expressed through breath and vibration.

What fascinates ethnomusicologists is the algoza's acoustical symmetry. Despite having separate air chambers, the pipes interact through a phenomenon called beat frequency, where slight tuning variations create pulsating overtones. Skilled players exploit this by adjusting lip pressure mid-performance, making the instrument sing in two voices that argue and reconcile, much like the call-and-response patterns of Sindhi folk poetry.

The crafting process itself is an exercise in precision asymmetry. Artisans in Punjab's rural workshops (dera) season the bamboo for years, ensuring stability. Six finger holes are burned into each pipe using hot iron rods – not drilled – to preserve fibrous integrity. "The left pipe's third hole must be 1mm wider than the right's," explains Ustad Ghulam Muhammad, a seventh-generation algoza maker from Bahawalpur. "This imperfection creates perfection in sound."

Modern players like Akbar Khamiso Khan have pushed boundaries by incorporating stainless steel fittings and synthetic reeds, yet preserve the instrument's symmetrical soul. During his groundbreaking 2019 performance at the Aga Khan Museum, Khan demonstrated circular breathing while playing both pipes in contrary motion – ascending one scale while descending the other – a feat requiring ambidextrous lung control that left audiences spellbound.

Scholars note the algoza's structural kinship with ancient Mesopotamian double clarinets depicted in Nineveh carvings, suggesting a migratory lineage along Indus Valley trade routes. Yet its persistence in Pakistan's musical ecology speaks to deeper cultural synchronicity. As Lahore-based musicologist Dr. Fauzia Farooq observes: "The algoza doesn't merely play notes – it performs the balancing act between individual expression and communal harmony that defines South Asian artistry."

Today, this humble shepherd's instrument finds new life in fusion projects, its symmetrical voice bridging tabla rhythms and electronic beats. When the algoza's twin pipes resonate across concert halls or dusty village squares, they continue their ancient dialogue – a testament to the enduring power of balanced duality.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025