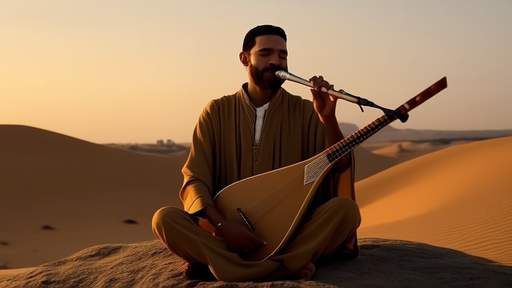

The buzuq, that long-necked lute so deeply ingrained in Levantine musical traditions, carries with it more than just melodies—it bears the weight of cultural refinement. In the narrow alleyways of Beirut's historic neighborhoods, where the scent of strong coffee mingles with the sound of distant traffic, one can still hear the buzuq's distinctive metallic twang drifting through open windows. This instrument, often overshadowed by its more famous cousin the oud in Western perceptions of Middle Eastern music, represents a particular Lebanese approach to sonic aesthetics—one that values subtle adjustments and microtonal precision.

What makes the Lebanese approach to the buzuq distinct lies in the details of its construction and playing technique. The instrument typically measures about a meter in length, with a pear-shaped body and a neck that seems to stretch impossibly long—often extending nearly twice the length of the body itself. This exaggerated neck allows for the wide spacing of frets necessary to accommodate the quarter tones so essential to Arabic maqam systems. But where Turkish or Syrian players might emphasize the buzuq's percussive possibilities, Lebanese musicians tend to draw out its lyrical qualities, using the extended neck to create fluid glissandos that mimic the human voice.

The craftsmanship of Lebanese buzuq makers reveals much about this cultural preference for nuanced expression. In workshops tucked behind Gemmayzeh's trendy bars or in the shadow of Tripoli's medieval mosques, luthiers carefully shape the soundboard from aged mulberry wood, believing its tight grain produces a warmer tone than the maple preferred elsewhere. The face is left slightly thicker than that of an oud, creating a brighter attack that gradually softens into sustain—a sonic metaphor, perhaps, for Lebanon's own blend of immediate passion and lingering melancholy. These artisans will spend days adjusting the placement of movable frets (typically 17-24 in number), testing each position by ear rather than adhering strictly to theoretical measurements.

This attention to microtonal precision speaks to a broader cultural value placed on refinement in Lebanese artistic traditions. Where other regional styles might celebrate the buzuq's raw, rustic qualities—evident in the Kurdish tanbur or Turkish saz—Lebanese players developed what scholars call "the Beirut style," characterized by meticulous ornamentation and controlled dynamics. The left hand doesn't merely stop strings at frets, but constantly adjusts pressure to bend pitches slightly sharp or flat, while the right hand's plectrum (usually a trimmed eagle feather quill) alternates between aggressive downstrokes and whisper-light upstrokes. It's an approach that mirrors Lebanon's historic role as a cultural intermediary—absorbing influences from surrounding regions while filtering them through its own sensibilities.

The buzuq's repertoire in Lebanon similarly reflects this ethos of subtle adaptation. While the instrument naturally excels at performing classical taqasim (improvisations) based on complex maqam scales, Lebanese musicians have gradually incorporated it into more contemporary genres. One can hear it adding gritty texture to alternative rock bands performing in Mar Mikhael's underground venues, or providing melancholic countermelodies in the orchestral arrangements of modern Arabic pop. This versatility stems partly from technical modifications—many Lebanese players now use nylon or carbon fiber strings instead of traditional brass, allowing for both classical precision and modern sustain.

Perhaps most telling is how the buzuq has become a symbol of Lebanese resilience. During the civil war, when Western instruments became difficult to import, the locally made buzuq experienced an unexpected revival. Musicians adapted its repertoire to express wartime experiences—lengthy improvisations gave way to shorter, more intense compositions reflecting the era's tensions. The instrument's durability (its metal strings and thick construction could withstand humidity and temperature fluctuations better than delicate violins or pianos) made it practical for performances in unstable conditions. Today, young Lebanese musicians are rediscovering the buzuq not just as a relic of tradition, but as a vehicle for contemporary expression—experimenting with electronic pickups, alternate tunings, and fusion genres while maintaining that essential Lebanese attention to microtonal detail.

In Beirut's music cafes, where the buzz of generators often competes with acoustic instruments, one can observe this evolution firsthand. Seasoned masters still perform the old muwashahat with flawless intonation, their left hands dancing across the frets with unconscious precision. Meanwhile, younger players push boundaries—perhaps running the buzuq through distortion pedals while somehow preserving those crucial quarter tones that give Arabic music its distinctive flavor. Both approaches share that characteristically Lebanese belief: that true artistry lies not in radical reinvention, but in the patient, precise adjustment of existing forms—the musical equivalent of perfecting a family recipe over generations by barely perceptible tweaks.

The buzuq's long neck, then, becomes more than a physical feature—it's a metaphor for the Lebanese artistic temperament. Just as the extended fingerboard allows for infinitesimal pitch adjustments, Lebanon's cultural history demonstrates a knack for subtle refinements rather than abrupt revolutions. In a region often associated with dramatic gestures, the Lebanese relationship with the buzuq reminds us that sometimes the most profound expressions come not from sweeping changes, but from knowing exactly where to place your fingers along that long, familiar neck.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025