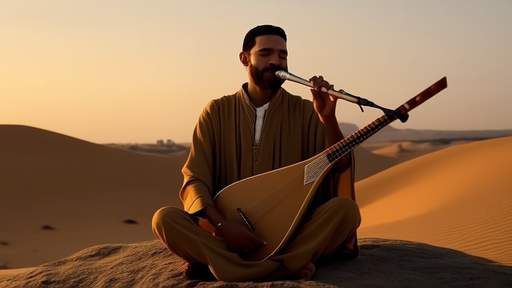

The resonant hum of a karnal—a traditional Omani copper trumpet—carries across the desert with a timbre unlike any other instrument. Its sound is both primal and refined, a product of centuries of metallurgical craftsmanship and acoustic intuition. The karnal’s voice is shaped not just by the player’s breath, but by the precise curvature of its copper tubing, a design choice that transforms raw vibration into something melodic. To understand how this works is to delve into the physics of bent pipes, the cultural weight of Omani metalwork, and the elusive alchemy of turning air into music.

Copper has been the material of choice for wind instruments across civilizations, and for good reason. Its density allows for a bright, penetrating sound, while its malleability lets artisans shape it into complex forms without compromising structural integrity. In Oman, where copper smithing dates back to the Bronze Age, the karnal’s design reflects generations of empirical acoustic knowledge. The instrument’s gradual bends aren’t merely decorative; they act as acoustic filters, suppressing certain harmonics while amplifying others. This creates the karnal’s signature tone—warm at its core but with a metallic edge that projects over long distances.

The physics of bent tubing reveals why even subtle curves alter an instrument’s voice. When a sound wave travels through a straight pipe, it reflects uniformly off the inner walls, preserving its original harmonic structure. Introduce a bend, however, and the wavefront distorts. High-frequency components—those responsible for brightness and articulation—scatter more aggressively as they ricochet around curves, while lower frequencies pass through with less interference. This explains why the karnal’s midrange dominates: its helical coils naturally attenuate extreme highs and lows, leaving a focused midband perfect for carrying rhythmic motifs across open terrain.

Omani craftsmen exploit this phenomenon through incremental adjustments. Unlike factory-made brass instruments with standardized radii, each karnal is hand-formed, its bends tweaked until the smith hears the desired balance between power and nuance. The process is as much art as science. Some artisans introduce slight ovalization to the tubing at key points, a technique that further modifies resonance by changing the cross-sectional shape. Others adjust wall thickness along the curve’s outer edge, where metal stretches thin during hammering, creating localized variations in vibrational damping. These micro-adjustments accumulate into a macro effect—an instrument that sounds distinctly Omani.

Modern acoustic modeling could likely reverse-engineer these principles, but the karnal resists full quantification. Its sound depends on variables beyond geometry, including the copper’s crystalline structure (affected by annealing temperatures) and even ambient humidity, which alters air density inside the bore. Performers add another layer of complexity through embouchure techniques like controlled lip buzzing, which interacts with the pipe’s natural resonances. What emerges isn’t just a pitched note, but a living texture—one that changes as the metal oxidizes over years, subtly shifting its mass and stiffness.

Today, as synthetic materials dominate instrument manufacturing, the karnal stands as a testament to copper’s irreplaceable sonic qualities. Its voice carries the history of Omani trade routes, where copper was currency, and deserts, where clarity of sound meant survival. When a player lifts the instrument to their lips, they’re not just making music—they’re activating centuries of acoustic wisdom, one bent pipe at a time.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025