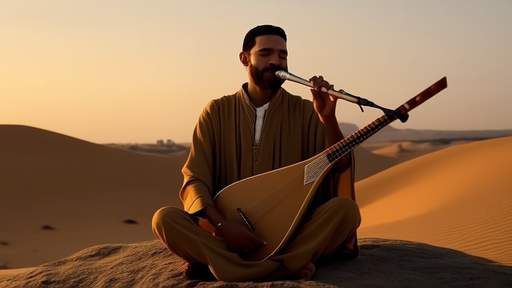

The art of crafting the pithkiavli, a traditional Cypriot reed flute, begins long before the instrument takes shape in the hands of a skilled maker. The process is deeply tied to the rhythms of nature, requiring an intimate knowledge of the land, the seasons, and the fragile ecosystems where reeds thrive. For generations, the gathering of reeds has been a quiet ritual, passed down through families and communities, preserving a connection to both music and the earth.

In the wetlands and riverbanks of Cyprus, the gathering season is dictated by the reeds themselves. Late autumn into early winter is the preferred time, when the stalks have matured but retain enough flexibility for crafting. Harvesting too early results in reeds that are overly green and prone to warping; too late, and they become brittle, losing the resonant quality essential for the pithkiavli's distinctive sound. Experienced gatherers move through the marshes with a practiced eye, selecting only the straightest, healthiest reeds—those free of cracks or insect damage.

The tools used for harvesting are often as simple as the process itself: a sharp knife, sometimes handmade, and a respect for the plant that borders on reverence. Gatherers work carefully, cutting at an angle to avoid damaging the root system and ensuring regrowth for future seasons. This sustainable approach reflects a broader philosophy—the understanding that the pithkiavli is not just an instrument but a living tradition dependent on the health of the land.

Once cut, the reeds are bundled and transported to drying areas, often shaded, well-ventilated spaces where they can cure slowly. Rushing this stage risks splitting or mold, ruining the reed’s acoustic potential. Over weeks, the gatherers monitor their harvest, turning the bundles periodically to ensure even drying. The sound of the finished flute hinges on this patience; even the most expertly carved pithkiavli will fall short if its reed hasn’t been treated with this deliberate care.

What’s often overlooked is the cultural weight carried by these gatherings. For many, the act of harvesting reeds is as much about community as it is about material. Older harvesters teach younger ones not just how to select reeds, but how to listen to them—how to test their density with a tap or judge their readiness by the way they bend. These moments, often unspoken, bind the craft to something larger than the sum of its parts.

Modern challenges have crept into this ancient practice. Wetland drainage and climate shifts have reduced prime harvesting areas, pushing gatherers to travel farther or adapt to thinner, weaker reeds. Some have begun cultivating patches privately, though purists argue that wild reeds, shaped by natural competition, yield superior instruments. The debate speaks to a tension between preservation and innovation, a theme echoing through many traditional crafts.

Yet, when a freshly made pithkiavli is played for the first time, none of this is visible. The music carries no trace of the labor behind it—only the clear, haunting tone that has defined Cypriot folk music for centuries. That sound is the final testament to the gatherers’ skill, a reminder that the simplest instruments often demand the deepest knowledge.

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025

By /Jun 6, 2025